|

| This post was peer reviewed. Click to learn more. |

| Image credit: Pxfuel |

Author: Christina Schramm, MSIV Medical Student

CASE PRESENTATION

A 31-year-old gravida 0, para 0 female patient presented to the emergency department with lower abdominal pain that started during sexual intercourse three days prior. She presented with abdominal distension, diffuse, constant, and cramping bilateral lower abdominal pain, referred pain to her shoulders, exertional dyspnea, orthostatic hypotension, and near-syncopal episodes. The patient reported constipation that turned to loose stools on day three. The patient denied fevers, vomiting, vaginal discharge or foul odor, vaginal bleeding, and dysuria. The patient had a past medical history of anemia and stated that her hemoglobin was within normal limits during her last routine blood draw. The patient had Mirena intrauterine device (IUD) inserted three years prior, and her last menstrual period was unknown. The patient had been in a mutually monogamous relationship with a male partner and stated no concern for sexually transmitted infection (STI). Differential diagnosis included IUD displacement, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian cyst rupture, ovarian torsion, and appendicitis.

In triage, the patient was afebrile with a blood pressure of 138/82 mmHg and a heart rate of 116 beats per minute (bpm). After six hours, her blood pressure dropped to 83/53 mmHg with a heart rate of 111 bpm. She was administered four liters of intravenous fluids, raising her blood pressure to 96/70 mmHg. Her complete blood count revealed a drop in her hemoglobin from 9 g/dL to 7.6 g/dL over the past six hours, increasing concern for acute hemorrhage versus vagal nerve irritation.

Physical exam revealed tenderness to palpation bilaterally in the lower abdomen without guarding, positive rebound tenderness, and mild distension. The genitourinary exam was unremarkable with no cervical motion tenderness or evidence of trauma, and her IUD was in place. The quantitative urine beta-human chorionic gonadotropin pregnancy test was negative.

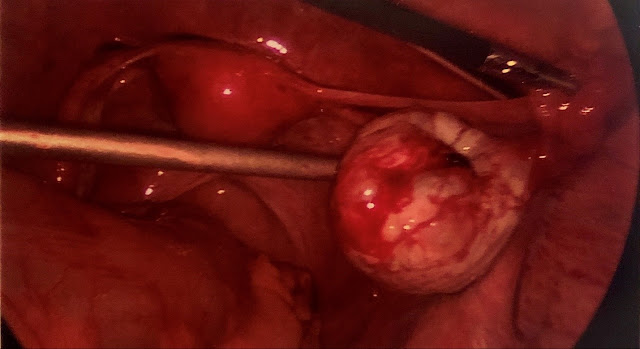

A computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a moderate volume of hemoperitoneum in the abdomen and pelvis with a moderate amount of hyperdense ascites greatest about the liver and spleen tracking into the paracolic gutter. Both CT and pelvic ultrasound demonstrated a cystic lesion in the right adnexa measuring up to 4.1 centimeters with a moderate amount of pelvic free fluid. Gynecology and general surgery were consulted. The patient was then taken to the operating room and underwent a laparoscopic right ovarian cystectomy (Figure 1) and a one-liter evacuation of hemoperitoneum. (Figure 2)

|

| Figure 1: Laparoscopic view of the right ovarian cyst before the specimen was extracted. |

|

| Figure 2: Free blood in the peritoneum during laparoscopic surgery. (a) 1 liter of blood was evacuated from the peritoneum. |

- Mohamed M, Al-Ramahi G, McCann M. Postcoital hemoperitoneum caused by ruptured corpus luteal cyst: a hidden etiology. J Surg Case Rep. 2015;2015(10):rjv120. Published 2015 Oct 1. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjv120

- .Larue L, Barau C, Rigonnot L, Marpeau L, Guettier X, Pigne A, Barrat J.

[Rupture of hemorrhagic ovarian cysts. Value of celioscopic surgery]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 1991;20(7):928-32. French. PubMed PMID: 1838758. - Senthilkumaran S, Jena NN, Jayaraman S, Benita F, Thirumalaikolundusubramanian P. Post coital hemoperitoneum: The pain of love. Turk J Emerg Med. 2018;18(2):80–81. Published 2018 Mar 23. doi:10.1016/j.tjem.2018.03.002

- Aacharya RP, Gastmans C, Denier Y. Emergency department triage: an ethical analysis. BMC Emerg Med. 2011;11:16. Published 2011 Oct 7. doi:10.1186/1471-227X-11-16